In this series, we’re highlighting the stories of people who remain connected to their home countries—either those with immigrant parents or those who are immigrants themselves. With “We Are All Immigrants: Stories About the Places We’re From,” you’ll hear from those most acutely affected by changing policies and a shifting reality, those who exist as part of multiple cultures at once. Here, Jessica Nabongo, founder and CEO of Jet Black boutique travel agency, and writer behind The Catch Me If You Can shares her story.

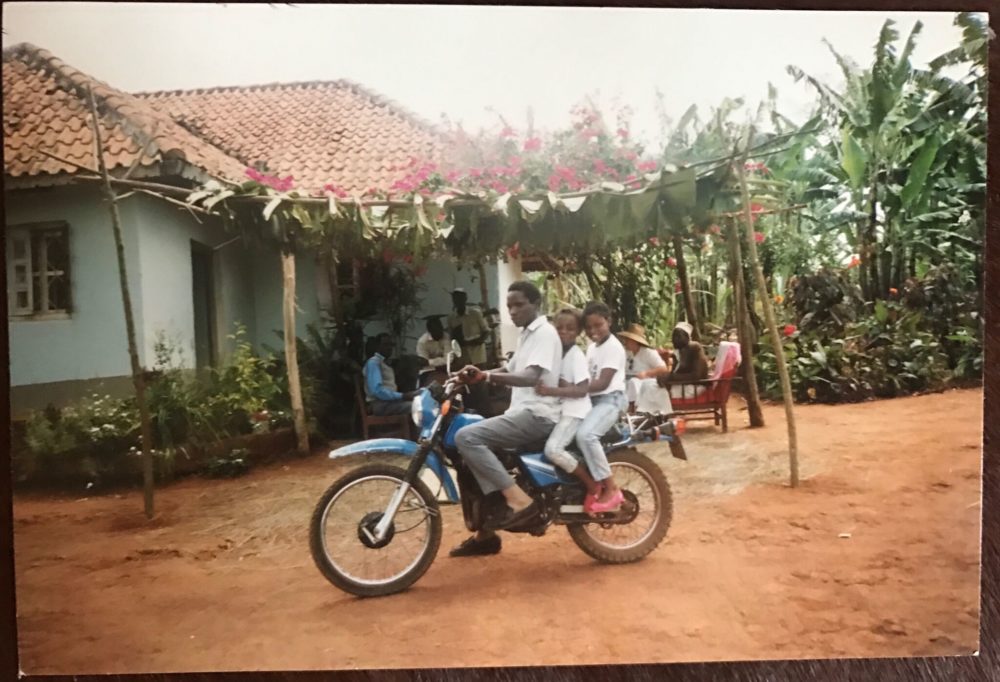

In the mid-afternoon, sun shining high above, after four hours along a bumpy Masaka Road, we arrived in Mbale. Things had changed. We no longer needed to walk part of the way; the road had been flattened a bit, enough. I remembered this place. Now I am here, my grandmother, or jaja, is not. I paid my respects, the ceramic tile only recently having dried in place. You could still see the footprints of the mourners.

They treated me like a muzungu, a regional term that means “white person.”

I checked in on my mother to ensure she was okay, though I knew she wasn’t. My father, the only man she ever loved, was about to be buried, and due to complications and distance, we arrived in Uganda one day after my grandmother’s burial. I was met by aunts, uncles, cousins, pigs, and chickens. Met by fresh avocado, pineapples, mango and the faint smell of eucalyptus. I was home, sort of.

In the markets of Kampala I searched for fabric and a new bag. I negotiated in English. They treated me like a muzungu, a regional term that means “white person.” I have the voice of a muzungu here.

Then, I was heading back home, another home. Wheels down, anxiety piqued, I prepared for immigration. My heart raced not knowing what questions they would ask, not knowing if I would be pulled out of line as I had been before. I was stopped. “Passport please.” Before reaching immigration, an armed member the United States military—my military—asked me, only me, for my passport. I questioned him. He demanded it. I questioned him again. He demanded it again, this time with his finger on the trigger of the military grade weapon in his hand. I gave in. He looked at my passport. I said, with attitude, “You didn’t think I was American did you?” He handed it back. He said nothing. I continued to immigration.

I am an American, but the world sees me as an African.

I am a native-Detroiter, a Michigander. I am a member of the Mutema clan, I am a Muganda.

I am an American, but the world sees me as an African—a non-specific, nondescript African. Before I speak, my American-ness is often erased by my hair cut, dark skin, high cheekbones, wide nose, and big lips. I am unmistakably African, but I have only briefly lived on the continent. My blood is purely Ugandan, but my birthplace and my accent, they are American. Inside of my American home I was raised as a Ugandan. Thanksgiving did not consist of macaroni and cheese and stuffing. We had matoke and benyebwa.

In 2008, I moved to Japan. I was American then. In 2009, I moved to London for graduate school; there, I was an American-born Ugandan. I moved to Benin in West Africa in 2010; there, je suis américaine mais mes parents sont ougandaise. I moved to Rome in 2011; there I was American because of my passport, but Ugandan inside the walls of the United Nations where I worked, where I could advocate for my ancestral continent.

As I regularly travel the world (very regularly: 36 countries in 2017, as of the end of August), I travel as an African, because that is how the world sees me. My second passport and my back tattoo specify that I am Ugandan. My accent and my primary passport are nods to America’s role in my life. As I continue to grow, learn, and explore this thing called identity, I realize that African, perhaps Afropolitan, is an identity befitting those of us born outside of our parents’ home country, and yet still feel tied to our specific cultures. Befitting those of us who feel a kinship with others like us: born of the continent but not on the continent.

—Jessica Nabongo